Flora Macdonald helped Boonie Prince Charlie escape to France after the disastrous Battle of Culloden

June 1746 saw Bonnie Prince Charlie in a pickle. On the run off the northwest coast of Scotland, he was in danger of capture and execution. But thanks in no small measure to a young woman named Flora Macdonald, he escaped.

June 1746 saw Bonnie Prince Charlie in a pickle. On the run off the northwest coast of Scotland, he was in danger of capture and execution. But thanks in no small measure to a young woman named Flora Macdonald, he escaped.

The prince, born Charles Edward Stuart, had landed in Scotland in 1745 with the intention of reclaiming the crowns of England, Scotland and Ireland for the House of Stuart. It was almost 57 years since his grandfather had been driven into exile, and it was time for the Stuarts to expel the “illegitimate” House of Hanover and take back what they considered rightfully theirs.

Things initially went well. The prince raised an army and proceeded as far south as Derby, a little over 100 miles (approx. 160 km) north of London. But that was the high point and the whole enterprise came a cropper at Culloden in the Scottish Highlands on April 16, 1746. Afterwards, it was a matter of fleeing for his life and ending up stranded on the Outer Hebrides with government forces in relentless pursuit.

|

| The tangled tragedy of Mary, Queen of Scots

|

| 19th century Scottish novelists cast a long shadow

|

| Popular historian Paul Johnson dead at 94

|

This was where Flora, a young woman in her early 20s, entered the picture.

The idea for Flora’s involvement originated with her stepfather and she was initially unenthusiastic. In addition to the danger of being caught aiding a fugitive, there was the question of damage to her reputation. For an unmarried young woman in mid-18th century Scotland, that wasn’t a trivial consideration. But despite those misgivings, she relented.

The scheme was for her to escort the prince – disguised as her Irish maid Betty Burke – by boat from the Outer Hebrides to the island of Skye. There, he’d be handed over to others and smuggled to the mainland for eventual rescue by a French ship.

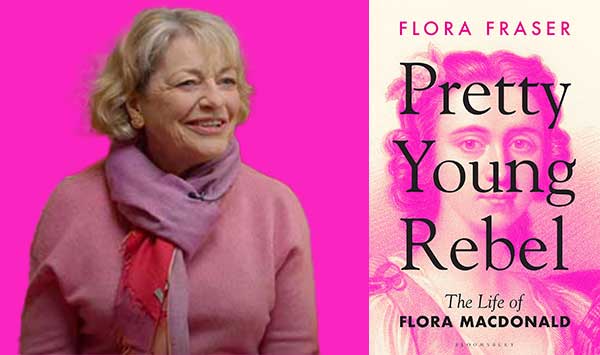

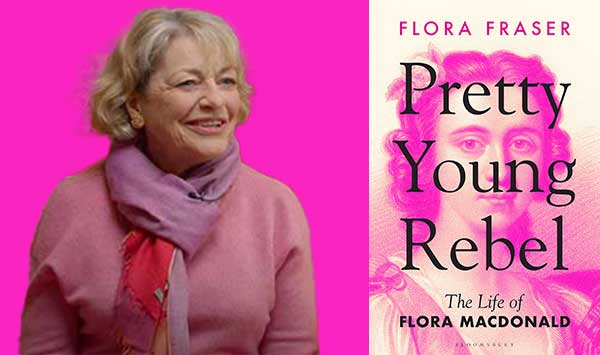

As recounted in a new book – Flora Macdonald: Pretty Young Rebel – the plan was easier said than done. Finally, though, they set sail on the evening of Saturday, June 28, 1746. In addition to Flora and the disguised prince, the boat included her male cousin and five male crew members.

Inclement weather and reduced visibility made the 30-mile (approx. 48 km) voyage both challenging and unpleasant. Still, they were on Skye about 12 hours later. Then, after navigating several more dangers, Flora was able to convey the prince to the safe hands of the Macleods of Raasay, who moved him off Skye on July 1. He eventually made it to France on September 30.

Flora’s adventures, however, weren’t over. Inevitably, the authorities discovered what had transpired and she was apprehended, questioned and sent to London for trial. But she got lucky. Very lucky.

Several of her captors took a paternal shine to her and recommended that she be treated kindly. En route to London by ship, she “was indulged the privilege … to call for anything on board, as if she had been at her own fireside.” Somehow, her helping the hunted prince was invested with a nobility of purpose that wasn’t granted to those who’d answered his call to arms.

Although confined while in London, Flora avoided actual prison. She also became a sought-after celebrity and acquired potential patrons from the ranks of wealthy Stuart sympathizers. She was back in Edinburgh in August 1747, a free woman with financial prospects.

She married three years later, by which point her patrons had delivered a tidy sum. To quote: “In 1746, the year the prince made Flora’s acquaintance … she had no dowry to offer a suitor. Now, thanks to her quiet determination to take advantage of her fame, she and Alan had a comfortable married home in the far northeast of the Trotternish peninsula on Skye.”

Unfortunately, Alan turned out to be a poor financial manager and, in 1774, they found themselves seeking a fresh start among North Carolina’s Scottish immigrant community. With the American Revolution brewing, their timing wasn’t great. Declaring for “king and country,” they chose the losing side and she was back in Skye by mid-1780, unwell and virtually broke.

Later in the decade, help came from an unlikely source. Hearing about her straitened circumstances, the Prince of Wales awarded her a pension. So, in her final days, the “pretty young rebel” who laid it on the line for the Stuarts was partially dependent on Hanoverian benevolence.

Flora Macdonald was a brave and resourceful woman. She was also shrewd enough to look reality in the face and do what was necessary to take care of her own and her family’s interests.

Nothing wrong with that.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.