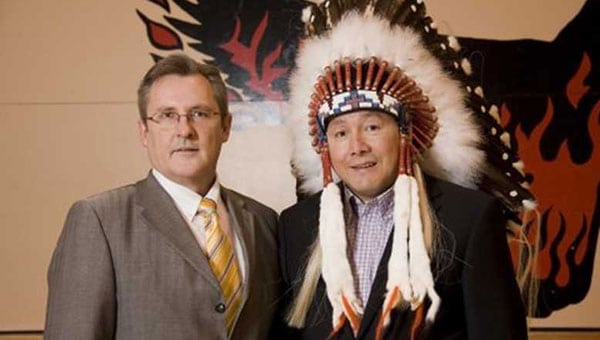

To Chief Reginald Bellerose of Muskowekwan First Nation in southern Saskatchewan, the wave of the future belongs to Indigenous entrepreneurship.

To Chief Reginald Bellerose of Muskowekwan First Nation in southern Saskatchewan, the wave of the future belongs to Indigenous entrepreneurship.

“Our entrepreneurial spirit has been dormant. We must re-ignite that spirit,” said Bellerose, the 13-year chief of the small Anishinaabe community on Treaty 4 territory.

For the 49-year-old, the key is changing laws to unleash Indigenous community potential, as well as changing attitudes within Indigenous communities, in governments and among business investors.

The longtime elected political leader has been promoting business development and community self-reliance for so long that he should be called a business leader. With his grandfather and uncle serving as chiefs of Muskowekwan and neighbouring Kawacatoose in the past, Bellerose said he has “100 years of leadership in his blood.”

While some families are involved in agriculture or other industries, Bellerose said his family has a legacy of leadership.

After taking political science and history at Concordia University of Edmonton, he studied project management at the University of Saskatchewan. Elected for the first time as chief of his community at age 35, he had already worked in the banking industry and in Indigenous education. He was also a negotiator for an Alberta First Nation on a power project.

Bellerose said that’s how he got his introduction to mega-projects. He also learned how to negotiate impact-benefit agreements.

“This is what gets me out of the bed in the morning, the politics and the projects,” he said. Besides being chief and a business leader in his community, he’s also involved in larger Indigenous economic initiatives. He’s chairman of the Saskatchewan Indian Gaming Authority, a representative political body of First Nations involved in gaming.

Bellerose is perhaps best known for his hard work in signing an agreement in early 2017 with Toronto-based Encanto Potash Corp. and the federal and provincial governments to create the first potash mine on First Nation land in Canada. The development led to an application of the First Nations Commercial and Industrial Development Act (FNCIDA). At the time, there was no regulatory framework for operating on First Nations lands. But there were 42 laws governing mining in Saskatchewan alone, he said.

Unlike what we often hear about other First Nations, this community welcomed mining development on their lands.

“We are pleased and excited to see Encanto commence potash exploration on our Muskowekwan First Nations lands,” he told the media. “The economic potential and benefits resulting from a potash mine has our entire community excited. The exploration agreements the Muskowekwan have with Encanto and the completed exploration program fully respect our treaty rights and stewardship of our land. We look forward to working with Encanto and moving this project forward.”

His enthusiasm for business activity on his First Nation stems from his intent to create own-source revenue so Indigenous communities aren’t dependent on the federal government.

First Nations, he said, must deal with the residential schools legacy, plus chronic health problems, addictions and grinding poverty. Indigenous communities need recurring revenue streams to deal with these challenges.

In their search for source revenues, he said they weren’t afraid to work with financiers in Toronto and New York.

“We need to teach these investors that First Nation lands can be brought into the economic mainstream,” he said.

“First Nations need to become a much bigger part of the Canadian economy.” The key, he said, is to be involved in economic projects in a meaningful way from the outset. They should not be “afterthoughts.”

Commercial investments on First Nations lands, he said, are hampered by unique challenges. The first is the political instability caused by the two-year chief and councillor terms imposed by the Indian Act. With such short terms, band politicians can’t engage in long-term planning and investment decisions because they’re constantly in election mode.

Bellerose also pointed out that the rules of the game don’t favour First Nation parties in economic development. The collective and controlled form of land ownership on reserves acts to “kill the value of your lands.” Property rights and mineral rights are insecure. Bellerose said the government must work with First Nations to improve the security of their lands.

“Our goal is to increase investor confidence and attract outside investment,” he said. First Nation band governments can help promote on-reserve entrepreneurship and business development by following the advice of the famous Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development. It promotes the separation of politics from business. Bellerose readily admitted that it’s “hard for the Nation to be a business entity.”

“You need to let the business do the business and the government do the government,” he said. “Most successful tribes have found the correct balance between politics and business.”

It’s a problem, he said, if the board of directors of band businesses are mostly populated by politicians. “There is no room for politics on these boards.”

Bellerose is insistent that First Nations must “operate at the speed of business, not the speed of government” when they’re seeking businesses to build revenue.

“In my experience, no one comes knocking at your door on your lands. You have to go out and self-promote your lands.”

Bellerose said resource development on First Nation lands is a delicate issue. He said he was careful to ensure that his community was involved and onboard. To seek that mandate, he said leaders must always engage with their membership and that’s not always easy. Resource development, he said, always involves an environmental impact.

“You must be very open about the costs. With potash mining, there is a salt pile left. There is a waste part and the tailings management issues. You have to explain that to the people. There will always be benefits but be open about the costs.”

Patient explanation to members is important. “You don’t want any surprises down the road.”

Bellerose also advised First Nations thinking of getting involved in resource development to “not skip on the legal advice.” He said that if you get poor legal advice at the outset, you’ll have mistakes that prove very costly in the long run.

He said the key for the future of resource development among First Nations is to shift from simply signing participation agreements toward full equity partnerships. There’s a large untapped market of talent in First Nation communities. Rather than companies seeking skilled labour offshore, these local First Nations members should be trained at home.

Bellerose believes these fundamental changes will lead to the necessary entrepreneurial culture in more Indigenous communities.

Joseph Quesnel is a research associate with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Joseph is a Troy Media Thought Leader. Why aren’t you?

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.