Before COVID-19, the craze for vegetable proteins was palpable. All we heard about were sustainability, animal welfare and Beyond Meat.

Before COVID-19, the craze for vegetable proteins was palpable. All we heard about were sustainability, animal welfare and Beyond Meat.

The health of the planet and well-being of animals became increasingly important factors to a growing number of Canadians, and it showed in the numbers.

A few months after the great confinement started, some new figures tell us that the interest in meat-free diets is still there.

In just four months, from February to July of this year, the popularity of major meat-free diets that don’t include land animal meat seems to have risen and continues to do so.

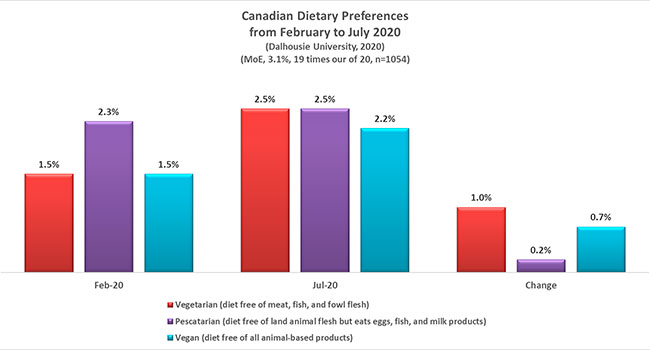

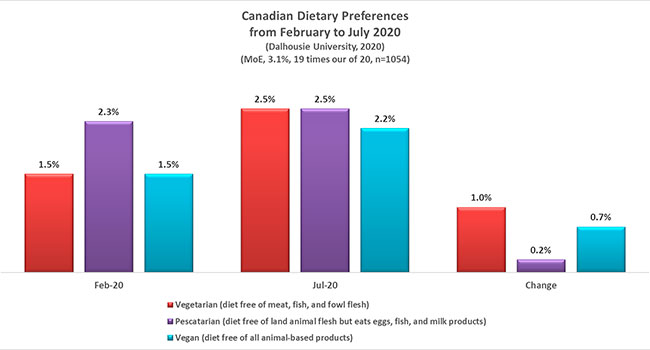

Dalhousie University surveys Canadians on eating trends almost every quarter. Comparing the last pre-pandemic survey (February 2020) with the first conducted during COVID-19 (July 2020), we’re able to see that rates of vegetarianism, pescatarianism (seafood is the only meat consumed) and veganism have increased.

Vegetarianism has increased from 1.5 to 2.5 per cent in a few months.

Pescatarism has also increased, according the recent survey. This diet, which is free of land animals but will include eggs and milk products, increased by 0.2 per cent.

The rate of vegan diets increased by 0.7 per cent. In other words, there are likely almost 600,000 Canadians who consider themselves vegan now and this is the highest measured rate in three years.

Of course, given the margin of error and numbers that remain relatively low compared to the rest of the population, the magnitude of these results must be taken with a grain of salt.

On the other hand, Canadians continue to be interested in diets that completely exclude land animal proteins.

Since March, when we were confined to our kitchens, the pandemic has certainly had an impact on our relationship with food. With the food service industry operating quite modestly for more than three months, domesticating ourselves and putting acute focus on cooking were the norm.

Each week had its interesting culinary trends. After the panic, peanut butter, and macaroni and cheese, we witnessed an extraordinary awakening of what using the kitchen was all about. Bread, pastry, pasta, meat – every week had its share of discoveries.

The agri-food industry struggled to keep up with us but it did.

Some experts have been saying that the pandemic will end the vegan and vegetarian movement for good. The anti-animal-protein rhetoric has dominated the industry in recent years and some believed the pandemic would bring most of us back to traditional culinary practices. Vegans would give way to omnivores and the proverbial meaty classics would take their rightful place.

But if the survey numbers are to be believed, this shift isn’t happening.

The pandemic has really hurt some sectors. Livestock, for instance, was greatly affected and farm animals were euthanized. More than a dozen slaughterhouses in Canada were temporarily closed when workers contracted COVID-19. Chickens, hogs and other livestock had to be slaughtered. It’s difficult to know exactly how many were wiped out, but limited access to packing plants became a problem and forced many producers to cull perfectly healthy animals.

The milk industry also had its share of misfortune. Millions of litres had to be dumped into sewers across Canada. Restaurant closures disrupted the agri-food sector and the demand for certain products such as ice cream completely change overnight.

Although Canadians were unsure of what to think about on-farm waste, more than 90 per cent of them believe it’s morally unacceptable to euthanize animals or throw away milk, especially when millions of citizens are newly unemployed.

The pandemic has demonstrated how fragile our food supply system is. Wasting mushrooms, lettuce or potatoes will be problematic. But animal and dairy production brings its share of morality and stakes are much higher when the supply chain is disrupted.

Producing food through animal breeding only to kill and dispose of them, whether intentional or not, is troubling. Period.

The continued popularity of meat-fee diets may point to the damaging legacy of COVID-19 for some sectors. Canadian consumers appear to still be looking for more protein options to put on their plates.

Despite these results, meat and milk are still popular for most Canadians, make no mistake. Restoring reputations should be top of mind for anyone working in livestock and dairy industries.

Dr. Sylvain Charlebois is senior director of the agri-food analytics lab and a professor in food distribution and policy at Dalhousie University.

Sylvain is a Troy Media Thought Leader. Why aren’t you?

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.