COVID-19 is causing panic across Canada. But before wringing our hands in anguish, we should put this crisis into a broader context.

COVID-19 is causing panic across Canada. But before wringing our hands in anguish, we should put this crisis into a broader context.

Places like universities, libraries, schools, churches, restaurants and pubs are closed. International flights are being redirected to just four airports with appropriate screening facilities, and the border between Canada and the United States is closed to all non-essential travel.

Essential services, grocery stores, doctors’ offices and hospitals are open – at least for now.

The country’s economy is grinding to a halt, while the health-care system is gearing up. Gearing up health care, as we know, requires considerable resources that can only come from a vibrant economy. But this problem is being pushed into the future.

Now we have a pandemic to fight – again.

To gain a broader context, a few statistics will help:

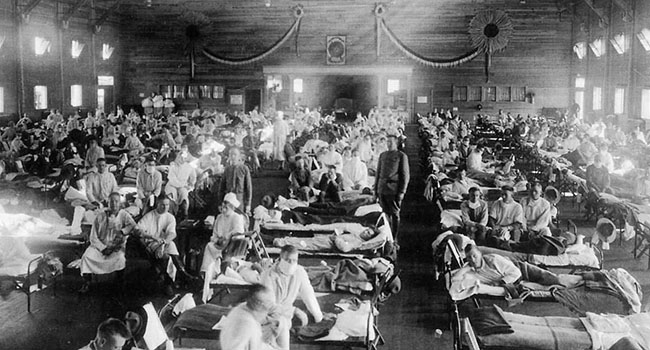

- The most devastating epidemic in Canadian history was the Spanish flu in 1918-20 that killed more than 50,000 Canadians. Even today, the common flu kills over 3,000 Canadians a year.

- In 1901, tuberculosis (TB) killed almost 10,000 Canadians out of a population of about 5.4 million. In 1947, when I was three years old, the death rate for TB was about 110 per 100,000 people.

- In 1945, a whooping cough epidemic killed about 25 per cent of infected babies under a year old. Infected children between the ages of one and two had a death rate of about 10 per cent, still very high but much better than 25 per cent.

- During the Second World War, approximately 7,000 young Canadian servicemen and women were killed every year; and every year, another 9,000 were wounded, many of them very seriously.

- In the early 1950s, a polio epidemic swept the nation, paralyzing about 11,000 people. The epidemic peaked in 1953 with about 500 deaths.

Of course, most Canadians are too young to have experienced these epidemics but many seniors still remember, as I do.

At the time of this writing, just over 1,000 Canadians have died from COVID-19, yet provincial governments have declared states of emergency. People are being asked to restrict their interaction with others in an attempt to slow the spread of the virus. If the epidemic is not slowed, the medical system may become overburdened. If this happens, many more people will likely die.

This is the worst-case scenario but no one knows what’s coming. The experts don’t even know.

We know, however, that epidemics are horrible things that cause unmeasured pain and suffering. But pain and suffering have been a natural part of human life since the Garden of Eden. It’s only in the last 150 years that scientific research, the development of effective water and sanitation systems, and modern medical care have made epidemics less vicious and more amenable to human intervention.

Hopefully, human intervention will slow or stop this pandemic before too long.

Throughout history, humans have survived countless diseases and illnesses. And we will survive this virus. Of course, some people will die, probably those who are most vulnerable, the old and infirm, and people with deficient immune systems. Thankfully, children are not as likely to die.

What should we do?

Remember the advice our parents or grandparents gave, which is similar to what public health officials are telling us. Avoid unnecessary contact with people, especially those who may carry the virus, wash your hands often and don’t cough on other people. Most importantly, keep a distance from other people so they don’t cough on you.

Hunker down in isolation for however long it takes for this disease to run its course. Read some good books, listen to great music and informative podcasts, talk to friends, meditate to ease the stress in your mind and body, and write letters to loved ones.

Above all, try to stay happy. Some things can’t be controlled.

For those who haven’t lived through previous epidemics, this will be a new experience, something they will tell their kids and grandkids. T-shirts will be printed with the slogan “I survived the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020.”

Some people are likely to have more difficulty as time passes. Unless they’re ill, they may think they’re not infected. Undoubtedly, some will spread the virus to others without realizing what they’re doing. When the pandemic is over, some people are going to feel guilty because of their careless behaviour. Others are likely to feel foolish because they overreacted. This is to be expected and clinical psychologists will be working overtime.

Even so, Canadians have survived terrible epidemics in the past and will survive this one, too.

Rodney Clifton spent 18 months in a sanatorium with TB meningitis starting in 1947, when he was three years old. He is a professor emeritus at the University of Manitoba and a senior fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Rodney is a Troy Media Thought Leader. Why aren’t you?

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.