Digital mental health treatment can work just as well as in-person therapy according to newly published research by a team of rehabilitation, psychology, psychiatry and military experts based at the University of Alberta.

The researchers carried out a scoping review of studies about mental health treatment delivered by telephone or computer to military members, veterans and public safety personnel, a designation that includes ambulance, fire, police, corrections officers and emergency services dispatchers.

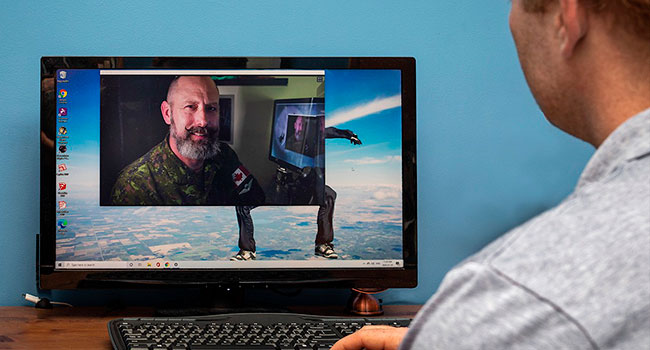

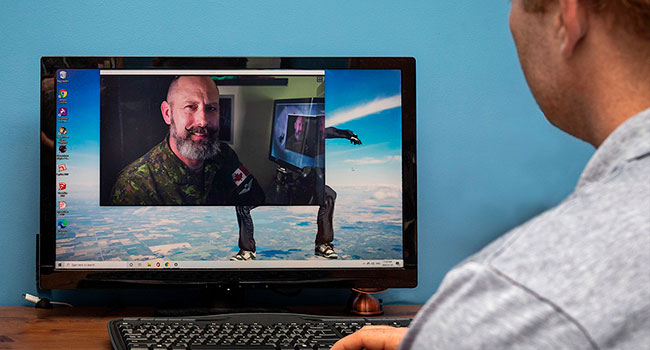

Remote mental health treatment can work as well as in-person therapy, according to U of A researchers who reviewed studies involving military members, veterans and public safety personnel. (Photo: Chelsea Jones)

“This is a group that tend to be affected by trauma that they experience in their work at a higher rate than people in other professions, whether they are in combat or in their day-to-day roles,” said lead author Chelsea Jones, an occupational therapist with the Canadian Armed Forces in Edmonton and a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine.

“Certainly COVID-19 can contribute to that – there’s more fear and potential exposure to the virus which might result in trauma,” said Jones, who also works with the Heroes in Mind, Advocacy and Research Consortium (HiMARC).

“On average, as well as for this specific population, we found that the outcomes for digitally and remotely delivered psychotherapy are just as good as the effects of face-to-face therapy,” said Phillip Sevigny, clinical psychologist and assistant professor of educational psychology in the Faculty of Education.

The team was given a COVID-19 and Mental Health rapid response grant through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research in response to the rapid shift to digital mental health services precipitated by COVID-19 this spring.

Sevigny noted that most of the studies they found focus on American military members and veterans. “That means there’s a great need for more research in a Canadian context, and particularly with our public safety personnel,” he said.

The next step of the project, already underway and set to report next month, involves interviews with 40 Canadians who are directly involved with digital mental health as patients, therapists or policy-makers.

COVID-19 has changed psychiatry forever

Jones noted that the literature review and early results from the interviews show that the convenience of digital mental health services is a benefit for many patients.

“The clients participating in their home experienced less stress and stigma, saved on travel time and transportation costs, and their missed work costs weren’t as great,” she said. “They were able to build a therapeutic alliance with the mental health providers, and the therapy drop-out rates were similar to in-person.”

At the same time, the researchers reported that the fact that rural Canada has poorer access to reliable Internet and cellphone services than urban areas can be a barrier for some.

“People living in rural and remote places are the ones we want to reach, yet these could be the same people who have challenges in terms of access,” Sevigny said.

Sevigny also noted it can sometimes be tough for patients to find a safe and private place in their home to do the “difficult work of therapy.”

“Children go running by, dogs bark, the connection breaks up, someone comes to the door, the phone rings,” he pointed out.

Another important consideration is what happens after a digital therapy session. While Jones said they found no evidence of increased suicide risk related to digital mental health treatment, “We have to take steps to ensure that if the client is in mental health distress as a result of the meeting, there is a support plan for when the camera turns off or the phone call is over.”

Both experts suggested clients and clinicians may need training to become comfortable with new technology. They also said more study is needed to learn how well some types of therapy work when delivered digitally, such as eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, which is used to treat post-traumatic stress injuries.

The research team plans to share the results with Veterans Affairs Canada, Edmonton and Calgary fire and police, and at the Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research Forum.

Jones said she hopes the findings will encourage clinicians and patients to gain confidence in virtual mental health services.

“While COVID forced our hand to switch to digital, my perspective as a clinician is that I’m surprised and elated at the positive outcomes we’ve found so far,” she said. “It’s good news.”

| By Gillian Rutherford

This article was submitted by the University of Alberta’s online publication Folio, a Troy Media content provider partner.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.