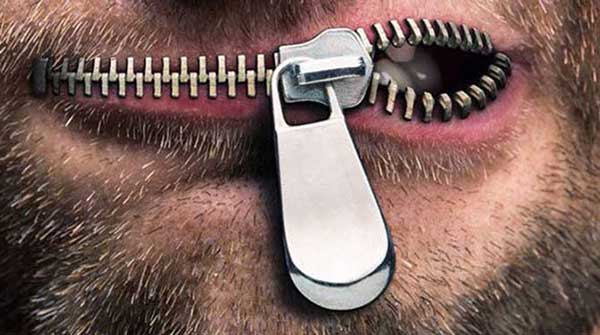

The controversy over comments made by Sen. Lynn Beyak illustrates that it’s virtually impossible to openly discuss Canada’s most important domestic issue: the chronic problems of poverty and unemployment in Indigenous communities.

The controversy over comments made by Sen. Lynn Beyak illustrates that it’s virtually impossible to openly discuss Canada’s most important domestic issue: the chronic problems of poverty and unemployment in Indigenous communities.

People who disagree with claims that the problem stems from Indigenous victimization – colonialism, bad governmental policy, discrimination, residential schools and the like – aren’t listened to. People who suggest that aspects of Indigenous culture stand in the way of progress are called racist.

Indigenous advocates don’t tolerate dissent and even the old war horses in the Conservative party, who should know better, have caved in to this politically correct pressure. The party has expelled Beyak from caucus.

Many very contentious issues have confronted Canadians over the years, from conscription to separatism. Many have been very complex and divisive. But to deal with any of these issues, a great deal of frank and open discussion – even heated debate – had to take place.

But this isn’t happening with Indigenous issues. Why?

Perhaps the main impediment to honest discussion is guilt. People feel guilty about the views they once held and the way Indigenous people were treated (often badly). They were an ignored and downtrodden people and we’re all guilty of failing to give them proper respect. The old racist stereotype of the lazy, drunken Indian retains such power and the ability to hurt today because not that long ago, it was mainstream thinking.

However, shutting down honest discussion won’t correct past wrongs. Now, more than ever, candid conversations are absolutely essential.

Maybe we should be openly confronting that stereotype rather than letting it prevent us from finding solutions to problems that have bedevilled the country since before we were even a country.

Make no mistake, I think the stereotype is false. Canada has a growing middle class of successful Indigenous people who have put the stereotype to rest for good. In most cases, they’ve completely integrated into the Canadian social system and economy without losing their Indigenous identities. They’ve demonstrated conclusively that a person’s race or ethnic origin has nothing to do with how hard-working or productive that person is likely to be.

But there’s a very large underclass of poor and under-employed Indigenous people in First Nations communities and in the raw parts of our cities. And alcohol abuse and reluctance to seek gainful employment are definitely problems. This isn’t a stereotype, it’s a fact.

How can this be explained? We don’t know because it’s not candidly discussed. Our mainstream newspapers and academics – people who should be frankly and openly discussing these issues – aren’t. There are countless articles and published papers about Indigenous people as victims, but there’s precious little about the very real problem of alcohol abuse and the reluctance of some Indigenous people to seek employment.

Here are two examples of Indigenous issues that aren’t being discussed:

Some years ago, a meat packing plant set up outside a city near my home. Part of the business plan was to employ the many unemployed Indigenous people in the region. The company went to great lengths to make this happen. Special recruiting and training procedures were used. Transportation was provided.

It didn’t work. The company had to recruit workers internationally because most of the Indigenous workers didn’t stay at their jobs.

As it turned out, the recruitment of workers from many parts of the world made the city a better place. However, while the company was recruiting elsewhere, the unemployment problem among Indigenous communities persisted.

There are probably many reasons why this happened, including the way our social assistance system is structured for Indigenous people, and the benefits that status Indigenous receive simply by virtue of their race. If a person finds that getting up early to catch a bus and work at a tough job five days a week is really not much more lucrative than simply staying home, that helps explain why the company’s efforts failed.

Or perhaps there’s something within the Indigenous hunter-gatherer culture that contributes to chronic unemployment in First Nations communities. In Hillbilly Elegy, author J.D. Vance talks of what appear to be habits of shiftlessness, and even laziness, among the people of “the hollers” of Appalachia. Those habits are due to cultural differences between the hillbillies and the mainstream culture, and aren’t personal defects. Could some of those same dynamics be at play in Indigenous communities?

Unfortunately, we don’t know why this bold experiment failed. To my knowledge, there’s been no serious effort to delve into the issue. The local newspaper should have made it a major issue. Academics at the local university should have devoted themselves to understanding what happened. Instead, there’s silence on what could have been a template for other regions with unemployed Indigenous people.

Another example of the Indigenous issue that gets scant treatment is alcohol abuse in many communities.

Manitoba has the highest rate of Indigenous child apprehension in the country. In most cases, the immediate problem is parental alcohol abuse. This has been the case for decades, although lately other drugs are involved as well.

Since the 1990s, Indigenous child welfare agencies have taken charge, but statistics show the number of apprehended children keeps climbing. And the factors that seem to drive these apprehensions – parental alcohol and drug use – remain unchanged.

The problem is made much worse by Indigenous women who continue to give birth to fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) babies in alarming numbers. At least half of the Indigenous children in care in Manitoba suffer from FASD.

Meanwhile, politicians pretend the problem can be solved by yet another rearranging of deck chairs on the Titanic.

In fact, politicians and Indigenous advocates have almost no control over this situation. And no amount of money or new government programs will make any significant difference.

The only thing that will work is if potential parents can be persuaded, shamed or forced to stop drinking.

An Indigenous child born with FASD has practically no chance to succeed, in care or left with their parents.

A parent who beats their child and causes permanent brain damage goes to prison. A parent who does the same thing to the child with a whisky bottle gets sympathy.

A few brave Indigenous authors have tackled the issue of alcohol abuse in Indigenous communities. Harold Johnson, in Firewater: How Alcohol is Killing My People (and Yours), describes how drinking is a way of life on some reserves. He claims that drinking is responsible for about half the deaths in many communities, including his own. Calvin Helin, in Dances with Dependency, takes a hard look at alcohol abuse, and the related victim mentality and the dependency mindset that cripple reserves.

But for the most part, these Indigenous voices are ignored. And when non-Indigenous authors try to deliver the same message, they’re vilified. Johnson makes the point that a non-Indigenous person who uses the words ‘Indian’ and ‘drinking’ in the same sentence are universally condemned as racist.

The institutions that should be crying out for real solutions to this awful child welfare problem and its direct connection to alcohol abuse – the media, universities, politicians – all prefer to talk about other things. Even the Conservative Party of Canada has made it clear that its members are to keep their mouths closed or stick to safe explanations.

Despite the considerable talk of reconciliation, it’s not possible with problems like these unsolved. And you can’t solve problems you won’t discuss.

Brian Giesbrecht is a retired judge and a senior fellow with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.