Bruce Willis’s diagnosis put a spotlight on frontotemporal degeneration and aphasia, but the facts are getting muddled

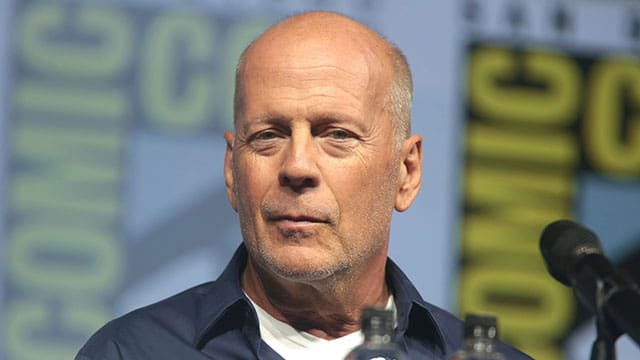

The family of actor Bruce Willis, best known for the Die Hard movie franchise, announced in 2022 that he was retiring from acting because he had a brain disorder that affected his ability to speak. Their statement called it aphasia, which is an acquired loss of language skills.

In 2023, the family updated Willis’s condition, saying it had since progressed and had been diagnosed more specifically as “frontotemporal dementia.” That description muddled some media reports and added to public confusion about an already complicated topic.

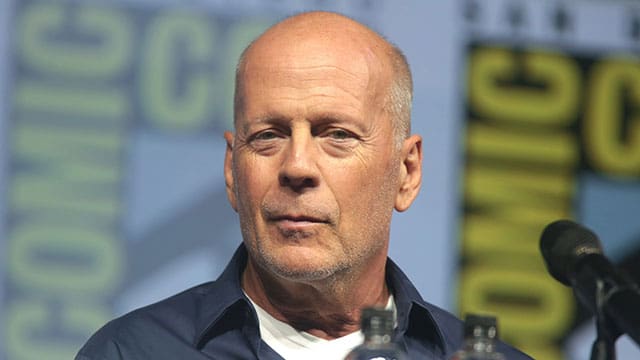

Esther Kim

The condition’s correct name is frontotemporal degeneration. It’s one of the underlying disease processes that can cause primary progressive aphasia (PPA), says Esther Kim, a speech-language pathologist, chair of the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders in the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine and member of the Neuroscience and Mental Health Institute.

The first thing Kim clarifies is that PPA is not a typical form of dementia. Instead, it is a rare condition in which the brain regions responsible for language are affected first. However, due to the underlying causes of PPA, dementia, including memory loss, eventually follows.

Bruce Willis. |

| Related Stories |

| Mild electrical stimulation could boost cognitive ability

|

| Why immune cells seem to cause brain damage

|

| Machine learning model able to detect signs of Alzheimer’s

|

Kim also points out that aphasia can have different causes. Typical aphasia is most often caused by strokes but can also result from brain tumours or traumatic injuries like gunshot wounds, car collisions or falls. On the other hand, PPA is a syndrome – a group of symptoms with different underlying causes – so it is often suspected when there isn’t an alternative explanation for a language impairment.

Here are some facts about PPA, which has only been clinically recognized for the past 15 years:

How common is primary progressive aphasia?

Primary progressive aphasia is a rare syndrome affecting one in 100,000 people, says Kim, referring to a 2022 study. It can be caused by several underlying disease processes, including frontotemporal degeneration, Lewy body disease or Alzheimer’s disease.

Those processes cause atrophy (shrinking) of brain tissue in the lobes behind the forehead and behind the ears, mainly in the brain’s left hemisphere – areas important for processing language.

How does PPA present?

Early symptoms involve problems with word-finding or the ability to summon the right word when communicating.

Depending on which subtype of PPA a person has and which parts of the brain are affected, symptoms can progress to trouble naming familiar objects and to errors in making the correct sounds for speech. But the word-finding symptoms alone can start as long as a decade before other symptoms present.

Who does it affect?

PPA usually presents at an earlier age than Alzheimer’s or typical dementia does, to people in their 50s and 60s.

“They’re at the height of their careers and so word-finding symptoms are often attributed to stress,” says Kim. “So, it can be misdiagnosed or sometimes brushed over.”

What side effects can PPA cause?

There is a known prevalence and an increased risk for depression among patients whose aphasia is caused by stroke because losing the ability to communicate can lead to a loss of employment and social networks. All of that also pertains to PPA, Kim says, but because it’s a progressive condition without a cure, depression is an even greater risk.

How is PPA treated?

If the PPA’s underlying disease process is Alzheimer’s, drugs for that disease may be used. But treatment usually concentrates on maintaining communication and quality-of-life functioning through psychological support and speech-language therapy. Kim’s department conducts clinics for patients with all types of aphasia, with group and individual programming to teach word-finding strategies and how to use non-verbal communication aids like gestures, notebooks, phone cameras and apps.

“We set them up in the face of the decline that’s going to come by solidifying the core vocabulary that’s important to them – things like family member names,” says Kim.

How can you reduce your risk?

As with dementia, there is no silver bullet. Researchers say that measures encouraged for reducing the risk of any dementia – eating a healthy diet, getting regular exercise, maintaining an ideal weight and being a non-smoker – certainly apply.

“More and more research is coming out showing that maintaining social networks is one of the biggest things to do to stave this off,” Kim notes. With social connections, she says, “you are communicating more, using your brain and challenging yourself.”

| By Helen Metella

This article was submitted by the University of Alberta’s Folio online magazine, a Troy Media Editorial Content Provider Partner.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.