Some conquests wiped out entire cultures and populations, leading to the collapse of their civilizations. Take Carthage for example

For interview requests, click here

Being conquered is never fun. Surrendering autonomy goes against the grain of human nature, and there’s invariably some loss of life and material possessions.

But not all conquests are the same. Indeed, many modern nations originated that way. Over time, victor and vanquished blended into a cohesive whole, sharing what came to be seen as a joint national story. England is just one case in point.

Then there’s the other extreme.

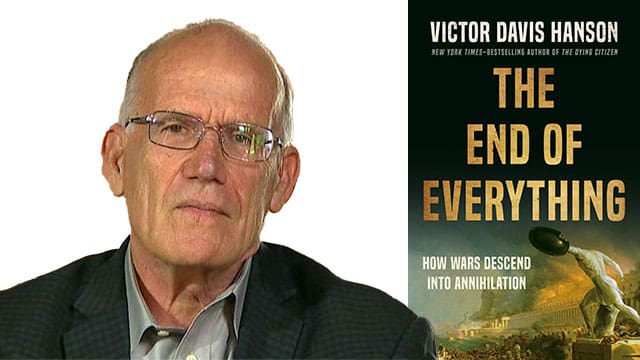

As historian Victor Davis Hanson tells the story, some conquests constituted “the erasure of an entire people’s way of life – and often much of the population itself.” In effect, “the end of cultures and civilizations.”

Hanson’s latest book – The End of Everything – offers four case studies. Organized chronologically from 335 BC to 1521, there’s “the levelling of Thebes by Alexander the Great, the erasure of Carthage by Scipio Aemilianus, Sultan Mehmet II’s conquest and transformation of Constantinople, and the obliteration of Tenochtitlan by Hernan Cortes.”

|

| Recommended |

| Treasure Island’s ripping adventure stands the test of time

|

| Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson were the dynamic duo of frontier justice

|

| The new book Deal With It explores the art of NHL trading

|

|

|

Because Roman history was a subset of Latin in my Irish high school, the discussion of Carthage particularly piqued my interest. Rome’s Cato the Elder put it succinctly: “Carthago delenda est!” (“Carthage must be destroyed!”). That’s the sort of thing that sticks in an impressionable schoolboy’s mind.

Ancient Carthage was a Phoenician colony created around 800 BC on the shore of what is now Tunisia. From there, it expanded into an empire ranging as far west as Sicily and Spain. And its interests inevitably bumped up against those of Rome.

The first of what history calls the Punic Wars ran for 23 years (264 to 241 BC), pitting Carthaginian naval power against Rome’s infantry legions in a contest predominantly about control of Sicily. Ever adaptable, Rome built its own formidable navy and ultimately prevailed, which resulted in both Sicily and Sardinia being annexed as Roman provinces.

The two sides went at it again in a 17-year war beginning in 218 BC. This time, the very existence of Rome was threatened after the Carthaginian general Hannibal crossed the Alps into Italy, scored a string of victories over a series of Roman armies and proceeded to ravage the peninsula for a number of years. Eventually, though, Hannibal was defeated, Carthage was stripped of its empire and reduced to little more than a city-state.

Rome, however, didn’t forget. Nor did it lose its ingrained fear and loathing.

So, a half-century later, when the power disparity had further widened in its favour, Rome deliberately set out to goad Carthage into conflict. The “problem” would be solved once and for all.

The resulting Third Punic War (149 to 146 BC) was vicious, fought on Carthaginian territory, and ended in Carthage’s total defeat. And the scale of the devastation was enormous.

A city population of perhaps a half-million at the beginning of the war had been reduced to around 50,000 by the time Carthage eventually fell, and those hapless survivors were sold into slavery. As for the physical city, it was levelled and abandoned until rebuilt by Julius Caesar a century later, after which it became one of the Roman Empire’s most important cities.

Although Hanson uses the term “annihilation” to describe Carthage’s fate, he’s not suggesting that every single Carthaginian died. Some small towns and isolated settlements in western North Africa survived in a semi-autonomous fashion and the Punic language stayed alive in rural areas. But Carthage no longer existed as a significant self-governing entity with a vibrant culture and prosperous trading presence. It had been effectively excised from the Mediterranean world.

Hanson notes several commonalities from his case studies, four of which strike me as particularly pertinent:

- Suddenness: When the end came, it came quickly. The “rendezvous with finality was often completely unexpected.”

- Payback: If your neighbours have significant grievances against you, they may see your moment of danger as an opportunity to exact revenge. The Spanish were certainly foreign interlopers in 16th-century Mexico, but that didn’t mean other indigenous communities were well disposed towards the Aztecs of Tenochtitlan. As Hanson puts it, “The degree of ferocity of the native besiegers who joined the Spanish could be explained by the considerable number of their own citizens who had previously been bound and had their hearts ripped out by the Aztecs.”

- You’re on your own: When Constantinople turned to European Christendom for help against its Ottoman besiegers, the response was woefully underwhelming.

- Deceptive impregnability: Just like Constantinople and Tenochtitlan, Carthage took undue assurance from the supposed impenetrability of its physical defences. But massive walls and towers only delayed the inevitable.

Perhaps there are lessons worth pondering.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.