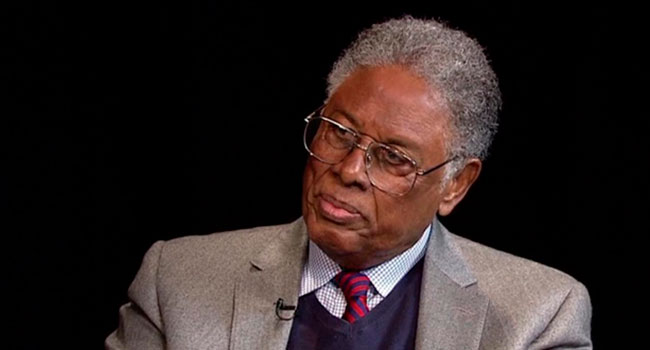

Thomas Sowell celebrated his 90th birthday this summer by publishing his 56th book.

Thomas Sowell celebrated his 90th birthday this summer by publishing his 56th book.

Entitled Charter Schools and Their Enemies, the book returns to one of his recurrent themes. He believes that the American public school system fails children from impoverished backgrounds by prioritizing the interests of teacher unions and their political sponsors.

In Sowell’s reckoning, American society needs to reacquaint itself with what should be a fundamental principle. Specifically, “schools exist for the education of children. Schools do not exist to provide iron-clad jobs for teachers, billions of dollars in union dues for teachers unions, monopolies for educational bureaucracies, a guaranteed market for teachers college degrees or a captive audience for indoctrinators.”

Sowell’s distinctiveness goes beyond his immense writing productivity.

As a libertarian conservative, he’s a minority in the economics profession. Stir in the fact that he’s Black and you get a rare bird indeed.

With his libertarian conservative perspective, Sowell emphasizes the value of free markets, competition, individual choice and personal responsibility. He’s correspondingly skeptical of prescriptive government, entrenched bureaucracy and concepts like racial preferences in university admissions and job recruitment.

All of this makes him controversial.

To his liberal critics, Sowell is an ideological warrior cherry picking data to score debating points. And the fact that he’s industrious, smart, knowledgeable – and Black – makes him a dangerous opponent.

Sowell was born in North Carolina but grew up in New York City. Unpromisingly, he dropped out of high school. However, he turned his life around after military service during the Korean War.

First came night school, followed by a series of economics degrees from prestigious universities. There was a bachelor’s from Harvard, a master’s from Columbia and a PhD from Chicago.

Along with university teaching, the life of a public intellectual beckoned, including a continuous flow of scholarly articles and books.

Even if I was familiar with all of the books – which I’m not – a full accounting would be way beyond the scope of this column. So I’ll just touch on a few.

Published in 1985, Marxism: Philosophy and Economics focuses on a long-standing Sowell interest. Marx was the subject of his Harvard thesis and several early scholarly articles.

It’s a densely-argued book, replete with discussion of topics like Hegelian dialectics and alienation. In the end, though, Sowell indicates that he’s travelled a long distance from his earlier Marxist sympathies.

He’s particularly critical of two aspects.

Marx’s theory of surplus value – that all value derives from labour and that profit is therefore an appropriated surplus – is deemed to be narrow, circumscribed and irrelevant to the modern world. To quote, “the Marxian contribution to economics can be readily summarized as virtually zero.”

Then there’s Marx’s take on alienation, which holds that capitalism has stunted personal development such that workers no longer understand their real interests. To Sowell, this is a natural facilitator for the acquisition and maintenance of political power whereby ordinary people are guided – or even coerced – by their betters.

The Vision of the Anointed (1995) also leans into this idea of special power for some.

Sowell believes that the range of what’s considered acceptable public discussion is effectively shaped by the prevailing orthodoxy among political, business, academic and journalistic elites. They’re the “so-called thinking people,” whom Sowell tags as “the anointed.” And their assumptions are taken for granted as the only legitimate way of looking at the world.

Language is thus used as a means of pre-empting issues rather than debating them. If “the anointed say that there is a crisis this means that something must be done – and it must be done simply because the anointed want it done.”

Conquests and Cultures (1998) concludes a trilogy started four years earlier, the common theme of which is that culture plays a critical role in the economic and social histories of different racial, ethnic and national groups.

Sowell’s use of the term culture doesn’t refer to music, poetry, storytelling or religion. Rather it’s about the form of human capital represented by attitudes toward work, education, entrepreneurship, innovation, property rights and the rule of law.

Whatever one thinks of Sowell, his industriousness certainly merits recognition. As fellow economist Walter Williams puts it, “My colleague not only writes when you and I are asleep or enjoying ourselves, but he might write with two hands.”

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps just a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.