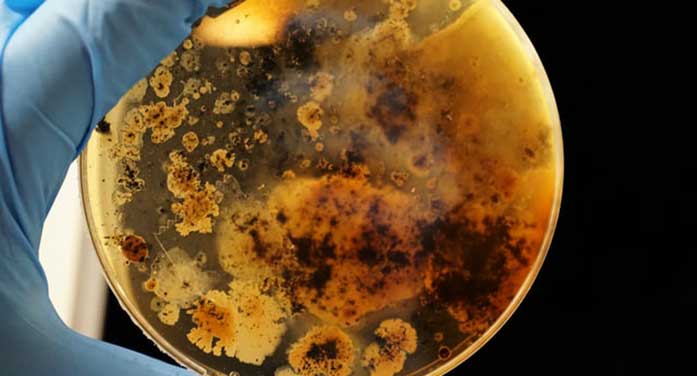

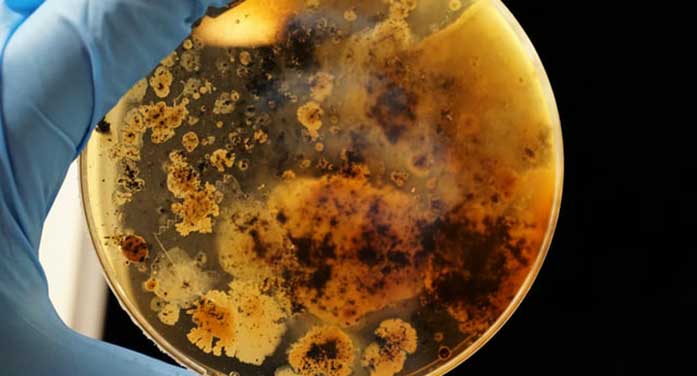

The way we treat wastewater could be leading to the emergence of water-treatment-resistant pathogens. Photo by Adrian Lange

A strain of Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria is not only surviving, it’s thriving in wastewater treatment plants, according to recent research from a University of Alberta-led team that’s now working to understand their potentially harmful impact on human health.

Most E. coli are destroyed by chlorine, oxygenation and other treatments in sewage plants. But the team found particular strains of pathogenic E. coli are left relatively unscathed.

“It’s like they’re wearing microbial Kevlar,” said principal author Norman Neumann, professor and vice-dean of the School of Public Health. “Genetically they’re very different and they are very adapted.”

Although most strains of E. coli don’t cause harm to humans, some have been linked to global increases in illnesses such as urinary tract infections, bloodstream infections and even meningitis, Neumann said. Some are highly pathogenic and are resistant to antibiotic drugs, and some are even resistant to heating at 60C – a potential worry for contamination of food during processing, he warned.

“Our paper is the first demonstration to show that what is coming out of a wastewater treatment plant and the survivors are potentially quite pathogenic and perhaps causing diseases that we haven’t typically thought about as being water-transmitted in the past,” Neumann said.

The study team isolated and analyzed the genetics of E. coli from raw and treated sewage samples from municipal wastewater treatment plants across Alberta.

Neumann is now encouraging organizations such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to carry out large epidemiological studies looking for broader patterns of illness in populations who are exposed to treated water.

“We need to understand the true scope of this problem by looking for manifestations of disease that go beyond the classic waterborne E. coli illness symptoms that we think of, such as diarrhea and gastroenteritis,” he said.

Does wastewater give early warning of COVID-19? by Geoff McMaster

Neumann noted that more study is needed to determine whether these pathogenic E. coli are present in drinking water, or whether people are mainly exposed by swimming in bodies of water downstream from treatment plants.

While antibiotics, hospitals and vaccines are important public health interventions, they are not as important as water treatment, he said.

“When you realize that drinking water treatment and sewage sanitation are the single biggest interventions we have to control infectious disease, and these bugs are breaching that barrier, what does it mean?” he asked. “Could there be a lot more disease being passed by water than we realize?”

Neumann’s research team is now looking for ways to improve disinfectant treatments for sewage, such as higher doses of chlorine, longer exposure to ultraviolet light, irradiation or higher heat treatment, while acknowledging that each new process would be costly and might turn out to be counterproductive.

“Could it be that our processes of treating wastewater are leading to the emergence of these water-treatment-resistant pathogens?” he asked. “Can we damage these E. coli enough so they can no longer evolve and repair? Or would increased treatment exacerbate the problem (by causing them to adapt again)?

“We know that nature usually responds to continued pressures that we place on it,” he said.

| By Gillian Rutherford for Troy Media

This article was submitted by the University of Alberta’s Folio online magazine. The University of Alberta is a Troy Media Editorial Content Provider Partner.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.