One of the benefits of teaching is that I get to make the final choice with regard to the books we study in class. With a greater emphasis on Indigenous content in the new British Columbia curriculum, I was drawn to Stoney Creek Woman, the story of Mary John.

One of the benefits of teaching is that I get to make the final choice with regard to the books we study in class. With a greater emphasis on Indigenous content in the new British Columbia curriculum, I was drawn to Stoney Creek Woman, the story of Mary John.

The Stoney Creek Reserve, today called Saik’uz First Nation, is not far from us, located just outside of Vanderhoof, B.C.

Quite honestly, the book was a joy to read for both me and my students. The story begins in 1918, when Mary is five years old. It ends 70 years later, with Mary reflecting over her life with author Bridget Moran.

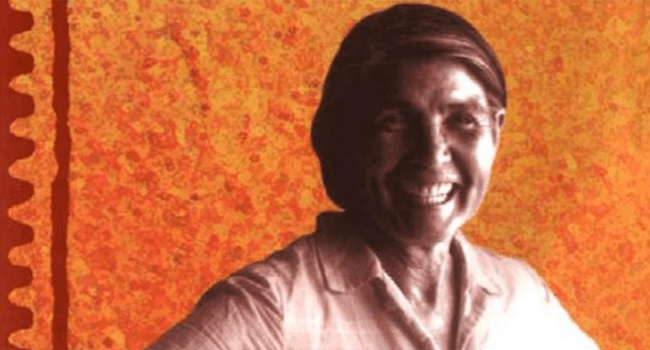

Mary John was a person we would call resilient. She faced a life of hardship, yet always focused on what she could do to improve the situation.

She was born to a 13-year-old Carrier mother who had been assaulted by an Englishman. Though he remained in the area, this man never even acknowledged Mary’s existence. Her mother fortunately married a wonderful man from Stoney Creek who loved Mary like his own daughter.

The story reflects the times Mary lived through. She experienced the traditional life of a Carrier child until she went to a church-run residential school.

Though she was not overtly abused in that setting and was well liked by the staff, it was very hard for her to be away from her family, away from her language and traditions. The little funding the school received from the Canadian government meant the food was horrible and the children spent more time doing manual work than they spent learning.

Mary’s mother finally risked the wrath of Canadian law and kept her daughter home when she was 14.

Two years later, Mary was married to Lazare John, a man she barely knew, in an arranged marriage. Lazare turned out to be a good man. He and Mary had 12 children and were together for over 60 years.

Life was difficult and several of their children died. In addition, the people of their community were subject to an archaic Indian Act, where the Indian agent had tremendous influence over the lives of people he clearly didn’t understand. The Great Depression and the tuberculosis epidemic also hit the people of Stoney Creek very hard.

Added misfortune was caused by racism in the legal system and the first cases of murder and disappearance in what is now called The Highway of Tears, which passes through Saik’uz territory.

Yet Mary always found a way forward. She worked much of her adult life to build bridges between the Carrier people and the non-Indigenous population. She was also a force for justice, helping to transform the Homemakers Association, founded by the Department of Indian Affairs to teach homemaking skills, into a vehicle for social change.

Mary and Lazare also worked tirelessly to pass on their traditional ways to the young people and to anyone who wanted to learn. She remarks on the irony of being asked to teach the Carrier language and traditions at the Catholic elementary school in Vanderhoof in the 1970s, yet she undertook it with great enthusiasm.

Later in her life, Mary received numerous public honours, including the Order of Canada.

The crowning achievement for me as a teacher was seeing how much my students loved and admired Mary John. Their final project was to simply create a work inspired by the book. Some reflected Mary’s activism and drew attention to the fact that the Highway of Tears still haunts us. Others beautifully demonstrated their love of this great woman in various original pieces.

We can be grateful to Moran for so beautifully writing Mary’s story. It’s a reminder that there are many such people among us.

May their resilience and determination always motivate and inspire us to continue the journey and build the kind of world they dreamed of.

Troy Media columnist Gerry Chidiac is an award-winning high school teacher specializing in languages, genocide studies and work with at-risk students.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.