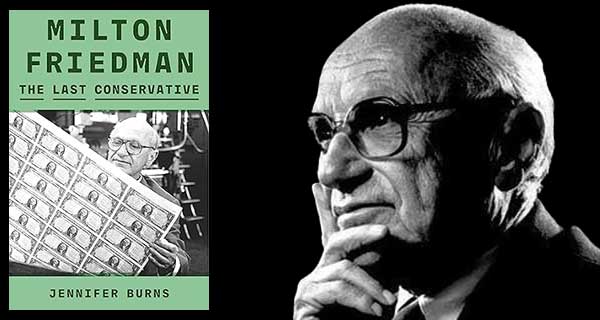

Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative unveils the controversial legacy of the iconic economist

Milton Friedman (1912-2006) is generally recognized as one of the 20th century’s two most influential economists, the other being the Englishman John Maynard Keynes. Friedman, though, is controversial in a way that Keynes isn’t.

Now, Stanford historian Jennifer Burns has produced a deeply researched biography entitled Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative. Although the “conservative” bit is a descriptor that she acknowledges Friedman would’ve rejected, it’s her best shot at placing him within the currently understood spectrum. And “last” refers to her assessment that Friedman’s particular synthesis of “free market economics, individual liberty, and global co-operation” no longer has the traction it once enjoyed.

The biography is by no means hagiographic. Indeed, you’d be hard-pressed to come away from it fancying Burns and Friedman as philosophical soulmates.

|

| More in Biography |

| Nixon in love

|

| Liberal disloyalty toward John Turner was truly shocking

|

| Cary Grant was a complicated, brilliant creation

|

Still, there’s an evident respect: “Friedman was fearless in his intellectual quest – never afraid to be wrong and, more important, never afraid to be unpopular.”

Friedman tackled the prevailing post-war orthodoxy about the appropriate role of the state in modern life. To many, this made him the wrong kind of maverick.

In an era disposed towards government intervention, Friedman’s ideological preference swam against the tide. On principle, he favoured reducing the extent to which the state could interfere with individual choices. Social engineering was anathema to him.

Within the economics profession, Friedman was a disrupter of conventional wisdom. He led the challenge to Keynesian activism, dismantled the highly touted Phillips Curve, and reintroduced money supply considerations to mainstream economic thought. If you’d built your career extolling the virtues of experts endlessly fine-tuning the economy and remodelling society, Friedman was a problem; perhaps even dangerous.

Nor did he hide his light under a bushel.

Of his voluminous academically-oriented output, 1963’s A Monetary History of the United States – co-authored with Anna Schwartz – was the most influential. But Friedman also made himself accessible to the general public. There was the regular Newsweek column and bestsellers like Capitalism and Freedom (1962) and Free to Choose (1980), the latter a collaboration with his economist wife Rose and conceived as a companion piece to their popular PBS television series.

Milton Friedman also worked hard at attempting to translate his ideas and prescriptions into public policy, which inevitably led to involvement with the political process. And when it came to influencing presidential candidates, Republicans were his natural audience.

Barry Goldwater was the first try, but it was doomed by Goldwater’s chaotically inept 1964 campaign. Then came Richard Nixon.

When Friedman met Nixon during the 1950s, he’d been impressed by Nixon’s intellect, but less so by other aspects of his personality. Nonetheless, he supported Nixon’s successful 1968 run and had reasonable hopes for influence.

In addition to now having a pipeline into the highest levels of economic policymaking, events on the ground were increasingly vindicating his diagnosis of what ailed the economy and what should be done about it. Management of the money supply was, he believed, the key to keeping inflation in check and facilitating sustainable growth.

Friedman was initially puzzled and alarmed by what he perceived as inappropriate monetary policy during the early years of Nixon’s presidency, feelings that graduated to betrayal when the administration turned to wage and price controls. He characterized the whole thing as a policy mishmash that wouldn’t work beyond the short term.

Friedman was right. By the mid-1970s, the era of chronic “stagflation” – that unholy combination of high unemployment and high inflation – had arrived.

Ronald Reagan was a different matter.

The two men became acquainted during Reagan’s California gubernatorial years and Friedman declared himself “very favourably impressed,” a sentiment returned in spades by Reagan. Describing the president’s reaction to Friedman, aide Martin Anderson was succinct: “His eyes sparkled with delight every time he engaged in dialogue with him.”

But there was a problem. To quote biographer Burns, “monetarism was built on data from a world that no longer existed … the land the New Deal built and inflation swept away.”

The monetary aggregates that Milton Friedman based his prescriptions on had been destabilized, partly by financial reforms implemented towards the end of Jimmy Carter’s presidency in a futile effort to cope with the rampant inflation Friedman had warned about. Consequently, the underlying relationships and definitions had changed, thus making the application of Friedman’s approach problematic.

It wasn’t a question of invalidating his central thesis about the importance of money supply management. It was just that applying it to the world as it had evolved was a more haphazard process than he’d imagined.

Milton Friedman, however, was about more than monetarism. That’s a topic for another column.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.