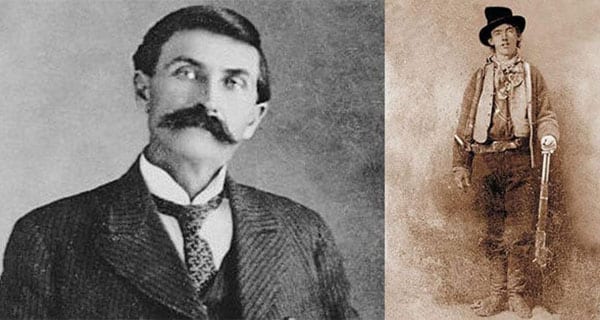

To the extent he’s remembered at all, Pat Garrett (1850-1908) is known as the man who shot Billy the Kid. Reputation-wise, it’s been a mixed blessing.

To the extent he’s remembered at all, Pat Garrett (1850-1908) is known as the man who shot Billy the Kid. Reputation-wise, it’s been a mixed blessing.

Although the shooting happened in Garrett’s capacity as a sheriff hunting down a convicted murderer, the fictionalizing of the Old West and the power of Hollywood storytelling often cast him as a villain, even a coward. As the narrative is frequently framed, he’s the man who shot his friend in circumstances other than a fair fight.

Garrett was born in Alabama and drifted west after the Civil War, arriving in what was then New Mexico Territory in the late 1870s. It was there that he met Henry McCarty, who also for a time called himself William H. Bonney and was subsequently known as Billy the Kid.

Garrett also married. In fact, he married twice. And like many Anglo men in the southwest, his wives were Hispanic.

Details of the first marriage are hazy. Some suggest the bride’s name was Juanita Martinez while others say it was Juanita Gutierrez. In any event, she died shortly thereafter, possibly in childbirth.

Garrett married again in 1880, this time to Apolinaria Gutierrez. The couple had eight children, one of whom – Elizabeth Garrett – became a well-known soprano and songwriter despite being born blind. The youngest child, a boy, survived until 1991.

Two criticisms gained traction after Garrett shot Billy on the night of July 14, 1881. One was that he had killed his friend and the other was that he’d done it in a cowardly way. Neither indictment is persuasive.

While the two men were certainly acquainted and had been occasional gambling companions, that doesn’t imply friendship of any depth. In terms of population, frontier settlements were small places. Everyone knew everyone.

As for the circumstances, it’s true that Garrett took Billy by surprise in a darkened room and thus violated the romantic concept of a fair fight. Or put another way, he didn’t give Billy a chance to shoot him first.

The non-romantics among us will be skeptical of this proposition. Whatever else he might have been, Billy was adept at killing people, having dispatched four men on a one-to-one basis and participated in the shooting of at least six others. The idea that you’d be morally obligated to give him a 50/50 chance borders on the absurd.

Garrett had his detractors during his lifetime, but the event that later turbocharged the narrative was the 1926 publication of Walter Noble Burns’ Saga of Billy the Kid. An instant bestseller, the book created a heroic image of Billy. Inevitably, Garrett’s reputation suffered.

After all, if Billy was a martyred and misunderstood hero, the man who shot him in the dark must have been a dubious character. Or at least someone to be decidedly wary of.

Hollywood, then in its infancy, took up the banner. The first post-Burns treatment – 1930s Billy the Kid – kicked off what was to be an extended run of mostly sympathetic, fictionalized renderings. I was an instantly smitten seven-year-old when the Audie Murphy incarnation introduced me to the subject.

Interestingly, Burns – the man who did so much to lionize Billy – acknowledged that Garrett’s reputation was unfairly maligned. To quote from a private 1928 letter: “In my estimation Garrett was a brave man – he must have been a brave man to do what he did – and what he did, it seems to me, resulted in a new era of law and order for New Mexico.”

Garrett’s later years were a mixed bag.

There were spells as a lawman, rancher and customs collector. There were also recurrent money problems. Finally, on Feb. 29, 1908, a gunshot blew away the back of his head on a lonely road in southern New Mexico. He was urinating at the time.

The question of responsibility for his death has never been satisfactorily resolved. The man who confessed claimed self-defence and was acquitted at trial. But various other names have been the subject of speculation, including a lurid tale of conspiracy concocted in an El Paso hotel room.

You’ll find many Billy the Kid markers in New Mexico today but relatively few references to Garrett.

Still, the woman running the office at the Masonic Cemetery in Las Cruces told me that the occasional traveller asks after the location of the gravesite where Garrett, his wife and seven of their children are buried.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps just a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.