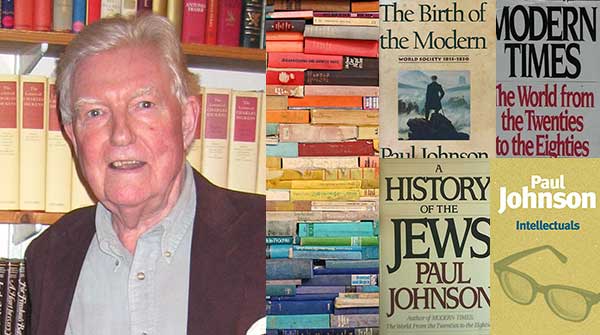

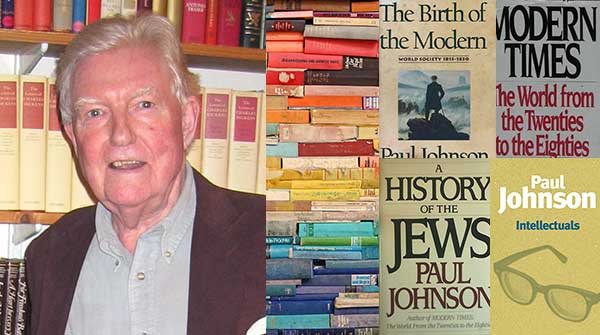

An enthusiastic polemicist with no qualms about giving voice to his particular perspective on the world

The English journalist Paul Johnson died on January 12 at the age of 94. In addition to being a columnist and author of popular histories, he was an enthusiastic polemicist with no qualms about giving voice to his particular perspective on the world. And, perhaps not surprisingly, that perspective shifted over the course of a long life.

The English journalist Paul Johnson died on January 12 at the age of 94. In addition to being a columnist and author of popular histories, he was an enthusiastic polemicist with no qualms about giving voice to his particular perspective on the world. And, perhaps not surprisingly, that perspective shifted over the course of a long life.

Johnson initially came to British attention as an unabashed man of the left. His first book – The Suez War (1957) – featured an introduction from Labour left-winger Aneurin Bevan and took a critical view of Conservative Prime Minister Anthony Eden’s failed Egyptian adventure. Published shortly after the debacle, it constituted an early statement of the case that led to Eden’s subsequent resignation.

Johnson’s ruminations were never short of an outlet. From the mid-1950s through to 1970, his perch at the weekly New Statesman meant that interested readers could always keep in touch with his opinions. The 1958 evisceration of Ian Fleming’s novel Dr. No got particular attention.

|

| Book Reviews |

| Liberal disloyalty toward John Turner was truly shocking

|

| 1889 book provides a way forward for Aboriginal policy today

|

| Margaret Thatcher and the end of apartheid

|

Under the heading Sex, Snobbery and Sadism, Johnson characterized Fleming’s latest James Bond opus as “the nastiest book I have ever read.” It displayed, he said, “the sadism of a schoolboy bully, the mechanical two-dimensional sex-longings of a frustrated adolescent, and the crude, snob-cravings of a suburban adult.” We can safely conclude that he didn’t like it!

Discussing his political migration from left to right, Johnson talked about his disillusionment with Britain’s predicament in the 1960s/70s and what he saw as the haplessness of its Labour governments: “The left had no answers. I became disgusted by the over-powerful trade unions which were destroying Britain.”

By 1981, he was ensconced as a weekly columnist at The Spectator, the conservative counterpoint to the New Statesman. It was a gig that lasted 28 years. And despite his prickly reputation, one of Johnson’s Spectator editors found him very easy to work with: “His copy was self-starting, to length, on time. It hardly needed editing.”

This professionalism facilitated an enormously prolific career. In addition to his regular journalism, Johnson authored over 40 books. On a good day, he would expect to produce between 3,000 and 4,000 words. As for the books, they varied in length from a short biography of Winston Churchill (192 pages) to sweeping histories clocking in well north of 800 pages.

Johnson ascribed his success as a popular historian to his experience as a journalist. Skill-wise, you acquire “the ability to condense quite complicated events into a few short sentences without being either inaccurate or boring.”

And journalism also inculcated a do-it-yourself habit of independence. He claimed to have “never employed research assistants of any kind,” referring to himself as “an old cottage industry.” He would do his reading, catalogue his findings on index cards and then use the cards as an organizing device for the book.

Although English, Johnson developed a significant American audience from the 1980s onwards. Modern Times (1983) was the catalyst.

Subtitled The World from the Twenties to the Eighties, the book got a lot of attention. The New York Times published a favourable review in June 1983, the famous philosopher Karl Popper was a big fan, and conservative commentators were hugely impressed.

The book’s main theme focused on what Johnson saw as the pernicious effect of the rise of moral relativism and the attendant decline in religious influence. Into the vacuum came the “will to power” and the arrival of “gangster statesmen.” Of these, Lenin was the most influential, being the 20th-century father of both totalitarianism and state genocide.

Johnson also made a contentious point about the danger inherent in the tendency towards steadily accreting state power: “The destructive capacity of the individual, however vicious, is small; of the state, however well-intentioned, almost limitless.” You can see why small government American conservatives became enamoured.

Among politicians, Johnson was probably closest to Margaret Thatcher. They’d been at Oxford together, he advised her in government and admired her proclivity to make up her own mind. Indeed, his self-description – “by nature a conservative with a strong radical bent” – could just as easily describe Thatcher.

Begrudgingly, the left-wing Guardian acknowledged Johnson’s talents in an acerbic, even snarky, obituary: “Though he lacked the character of a real scholar, he was clever and widely read, with an old-fashioned well-stocked mind, so that he could turn out a polished column on almost any subject full of apt examples and pithy phrases.”

Given the opportunity, one wonders what “pithy phrases” Johnson would’ve deployed in response.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.