One thing we’ve learned this year is that global pandemics have a big impact on teaching and learning.

One thing we’ve learned this year is that global pandemics have a big impact on teaching and learning.

In mid-March, regular kindergarten-to-Grade-12 classes across Canada were suspended and instruction moved online.

While schools in some provinces partially reopened in June, this doesn’t mean things are back to normal just yet. Students gained limited access to schools in order to meet with teachers and complete assessments but regular in-class instruction in most provinces won’t resume until fall.

However, some politicians apparently want fall classes to be suspended as well. For example, Manitoba NDP Leader Wab Kinew recently posted a tweet asking why the Manitoba government was planning to resume regular classes in schools this fall when colleges and universities were putting their courses online.

The answer is obvious: kindergarten-to-Grade-12 students aren’t university students. There’s a world of a difference between a first-year university student taking a biology course and a Grade 1 student learning how to read for the first time. Anyone who works with children in school would know this.

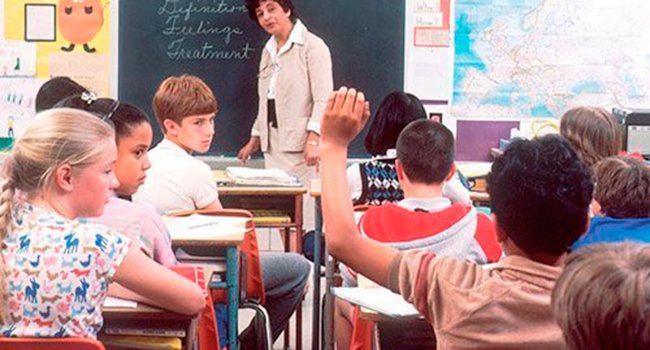

Students learn best when they develop strong personal connections with their teachers. The only reason emergency remote learning wasn’t a total disaster this spring was because teachers could lean heavily on the relationships they had built with students over the course of a school year.

It’s a lot more feasible to finish a school year using remote learning than it would be to start a school year this way.

The same is true of hybrid measures such as staggered school days where students attend school on a rotating basis and do the remainder of their learning at home. Not only would this be a logistical nightmare for schools, its effectiveness would be limited.

That’s because physical distancing measures at school are more symbolic than anything else. Kids will come into contact with each other during the school day no matter what rules we put in place.

Fortunately, the best scientific evidence now indicates school-age children are less likely to contract COVID-19 or develop serious complications from the virus than anyone else. If it’s safe for children to visit grocery stores and hang out in malls, it should be safe for them to attend school.

In addition, we need to stop dwelling on worst-case scenarios and instead look at the local context. In most areas of the nation, the active COVID-19 caseload remains exceptionally low. The whole point of physical distancing restrictions was to flatten the curve so our hospitals don’t become overwhelmed with critically ill patients. So far, that goal has been achieved.

Even so, COVID-19 isn’t going away anytime soon. Most experts say it will be at least a year, and probably much longer, before a COVID-19 vaccine becomes available. Obviously, students need to get back to regular classes a whole lot sooner than that.

While we want to keep students safe, it’s important to recognize that safe doesn’t mean zero risk. Everything we do in life involves some level of risk. There has never been a time in history when schools have been completely risk-free.

Canadian students have missed out on enough learning this year. By the time fall arrives, let’s hope students are back in regular classes.

Michael Zwaagstra is a public high school teacher, a research fellow with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy, and author of A Sage on the Stage: Common Sense Reflections on Teaching and Learning.

Michael is a Troy Media Thought Leader. Why aren’t you?

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.