By Gerry Bowler

and Rod Clifton

Frontier Centre for Public Policy

The string of calls for public apologies continues unabated. How many apologies are enough?

Yet again, demands have been made that Pope Francis apologize for the role that the Catholic Church played in the Indian Residential School system. His refusal to do so has outraged native leaders. Anishinabek Nation Grand Council Chief Patrick Madahbee denounced “predatory abuse in biblical proportions” and “the church’s heinous crimes,” saying that a papal apology was necessary “before considering any kind of reconciliation.”

There has been no shortage of regrets expressed by the churches involved in the residential school system. The United Church first said they were sorry in 1986, the Anglicans apologized in 1993, the Presbyterians in 1994 and the Mennonites in 2010. The United Church apologized again in 1998.

So why has the Catholic Church refused to say it was sorry?

Actually, the Catholics have apologized – at numerous times and in numerous places.

In a 1991 national meeting in Saskatoon on the residential school system, Canadian Catholic bishops and leaders of male and female religious communities issued a statement. “We are sorry and deeply regret the pain, suffering and alienation that so many experienced,” at the residential schools, said the statement.

The church acknowledged its failures again in 1995 in a brief to the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. The Oblate order issued its own apology in 1991, followed by the archbishop of Halifax in 1993, the archbishop of Grouard-McLennan in 2008, the bishop of Mackenzie-Fort Smith in 2009 and a representative of female religious orders in 2013.

But what about the Vatican?

Pope John Paul II, during his 1984 and 1987 visits to Canada, acknowledged Catholics mistakes in addresses to Indigenous peoples and called for a “new covenant” with natives.

Pope Benedict XVI in 2009 said he was sorry for the history of abuse and “expressed his sorrow at the anguish caused by the deplorable conduct of some members of the church.” Native leaders welcomed this apology. Chief Edward John of the Tl’azt’en First Nation said that an emotional barrier had been lifted; Phil Fontaine, national chief of the Assembly of First Nations, said that the Pope’s words had given him comfort.

The continual clamour for yet another apology, this time from Pope Francis, leads one to wonder whether the process of regret and reconciliation shouldn’t work in both directions.

If apologies are truly necessary to bring about reconciliation between the races, then perhaps it’s time to consider some of the atrocities that natives have committed and to demand some expressions of repentance from their present-day representatives.

Let’s begin with the worst massacre in Canadian history. This was the genocidal campaign from 1647 to 1649 by the Iroquois Confederacy against the Huron nation. In the course of this series of attacks, perhaps as many as 30,000 Hurons were killed, with a remnant of survivors fleeing to New France for protection. These killings, and those of the Jesuits who ministered to the Hurons, are today remembered at the Huron/Ouendat Village and the Martyrs’ Shrine near Midland, Ont. Would it be asking too much for present-day Canadian Iroquois to apologize to the descendants of the Huron and to the Jesuit order?

The worst mass murder of whites by natives occurred in the early morning hours of Aug. 5, 1689, when more than 1,000 Mohawk warriors descended upon the French-Canadian settlement at Lachine, near Montreal. They set fire to the village, murdered many of its inhabitants and retreated with a number of captives. The fate of these prisoners is described in an 18th-century history:

“After this total victory, the unhappy band of prisoners was subjected to all the rage which the cruellest vengeance could inspire in these savages. They were taken to the far side of Lake St. Louis by the victorious army, which shouted 90 times while crossing to indicate the number of prisoners or scalps they had taken, saying, ‘We have been tricked, Ononthio [the governor of New France, Count Frontenac], we will trick you as well.’ Once they had landed, they lit fires, planted stakes in the ground, burned five Frenchmen, roasted six children, and grilled some others on the coals and ate them.”

As many as 48 prisoners were tortured to death. We call upon the Mohawk Council of Kahnawà:ke to repudiate this policy of murder by their ancestors and to issue an apology.

Samuel Hearne, the English explorer, made an expedition to the Arctic Ocean by way of the Coppermine River. On this trek, he was joined by a group of Dene who were intent on making war against their Inuit enemies. Near a waterfall on July 17, 1771, these natives attacked a sleeping band of Inuit and murdered them in what came to be known as the Massacre at Bloody Falls. In Hearne’s description:

“In a few seconds the horrible scene commenced; it was shocking beyond description; the poor unhappy victims were surprised in the midst of their sleep, and had neither time nor power to make any resistance; men, women, and children, in all upwards of 20, ran out of their tents stark naked, and endeavoured to make their escape; but the Indians having possession of all the land-side, to no place could they fly for shelter. … The shrieks and groans of the poor expiring wretches were truly dreadful; and my horror was much increased at seeing a young girl, seemingly about 18 years of age, killed so near me, that when the first spear was stuck into her side she fell down at my feet, and twisted round my legs, so that it was with difficulty that I could disengaged myself from her dying grasps.”

Naturally, present-day Dene will want to make amends to the descendants of the victims of their brutal forbears.

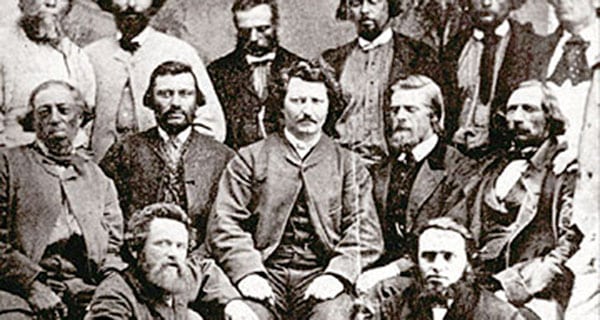

In 1869, the Métis of the Red River area rose in revolt against the claims on their territory (newly surrendered by the Hudson’s Bay Co.) to the government of Canada. A provisional regime led by Louis Riel rounded up opponents of this move and imprisoned them. One of the dissidents, a 28-year-old Irish immigrant named Thomas Scott, was court-marshalled and executed by firing squad in March 1870. We call upon the Manitoba Métis Federation to disavow this extra-judicial murder and to issue an apology.

During the second uprising led by Riel, the Northwest Rebellion of 1885 in Frog Lake, in what is now eastern Alberta, a group of Cree warriors led by Wandering Spirit raided the Hudson’s Bay Co. store. They also took a number of Canadian settlers and officials prisoner and burned down the village. They subsequently murdered the Indian agent, two Catholic missionaries and their assistant, and five other white men. We call upon the Frog Lake First Nation and the Assembly of First Nations to recognize this dark deed and to apologize.

If, as we are forever told, apologies must freely flow if reconciliation is to be achieved in Canada, there should be no hesitation on the part of native groups to issue their regrets for these bygone evils.

Or – and here is a shocking new idea – we could all assume that present-day Canadians are not responsible for actions undertaken in earlier days and have no need to apologize.

We could assume that our fellow-citizens wish us well, regardless of ancestry, and get on with building a unified nation, free of inherited resentments.

Rod Clifton is a sociologist and Gerry Bowler is a historian. Both are Senior Fellows of the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.