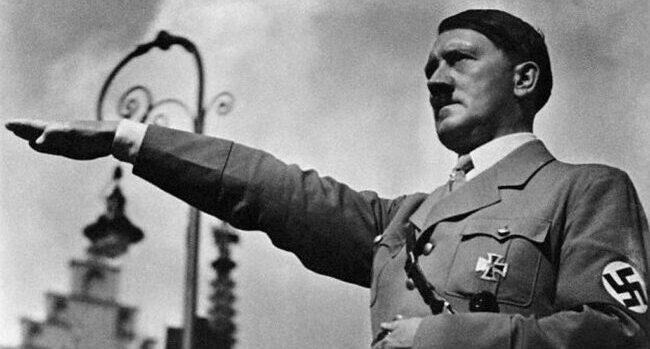

Adolf Hitler began 1941 in a commanding position. He had 10 European conquests under his belt and just one active foe – beleaguered Britain and the members of the Commonwealth, like Canada. But by year-end, he’d added the Soviet Union and the United States to his slate of antagonists. And the declaration of war against the United States was a fateful choice.

Adolf Hitler began 1941 in a commanding position. He had 10 European conquests under his belt and just one active foe – beleaguered Britain and the members of the Commonwealth, like Canada. But by year-end, he’d added the Soviet Union and the United States to his slate of antagonists. And the declaration of war against the United States was a fateful choice.

Hitler had, in effect, manoeuvred himself into a no-win position. While he could score tactical victories, the long-term calculus had turned against him. As historian Victor Davis Hanson relates in his book The Second World Wars, ultimate victory for Germany was now “beyond Hitler’s grasp.”

The combined population of the United States, the Soviet Union and Britain was more than double that of Germany and its Italian and Japanese allies. And with the United States in the war, its industrial resources generated a continuous flow of the materials needed to win an all-out 20th century conflict.

Victory required the ability to destroy the industrial base and population centres of the enemy. Hitler certainly had the will but he didn’t have the capacity. And he had no prospect of getting it.

To quote Hanson: “In an existential conflict, the strategy must consist of destroying an enemy’s ability to make war. Hitler declared war in 1941 on the United States and the Soviet Union with an air force (and navy) that had been unable to destroy or capture Britain, and certainly could not reach Russia beyond the Ural Mountains – or harm New York, Detroit, or San Francisco.” In contrast, once fully up and running, the Americans had the “ability to bomb and destroy” the German homeland.

Why, then, did Hitler declare war on the United States just four days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour? Why didn’t he at least wait to see if the Americans were going to declare war on Germany?

It was a decision Hitler didn’t have to make. But he made the choice quickly, enthusiastically and with little consultation.

In his book Fateful Choices, English historian Ian Kershaw takes us through the background to Hitler’s thinking, arguing that “Given his underlying premises, his decision was quite rational.”

Hitler had long held the view that conflict between Germany and the United States was inevitable. Germany would come to dominate Europe and America would eventually want to complement its economic power with an outward-looking foreign policy. So the two giants would clash. That, in Hitler’s mind, was how the world worked.

However, that was for further down the road. Perhaps much further down the road. And maybe not even in Hitler’s lifetime.

The situation changed with the outbreak of war in September 1939. Although officially neutral, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s American administration clearly favoured the British and took increasingly overt measures to provide assistance.

But there were significant political limits to Roosevelt’s freedom of action. Public opinion had a strong isolationist component and there was enormous skepticism about being sucked into a war that many Americans felt was not their concern.

So Hitler played it carefully, insisting that his U-boat commanders go to extreme lengths to avoid sinking any American ships, even if those ships were facilitating supplies to Britain. The naval leadership wasn’t happy but there was to be no provocation that might give Roosevelt an excuse to bring the U.S. into the war. While direct American involvement might eventually be on the cards, it should be postponed as long as possible.

Hitler also sought an insurance policy by encouraging Japan to do something in the Pacific, thereby providing a distraction for the Americans. With the distrust between America and Japan, even a Japanese attack on British Singapore might do the trick.

But when Japan surprised everyone – including the Germans – by bombing Pearl Harbour, Hitler’s “underlying premises” gelled. If Roosevelt’s pro-British inclinations were expediting the inevitable conflict with the U.S., Hitler would take the initiative and aggressively support Japan to ensure that it tied up the Americans in the Pacific.

Hitler, however, had another option, albeit a brazen one that would have required abandoning his “underlying premises.”

He could have invoked racial solidarity and declared war on Japan in support of the United States. Had he done so, he might have kept America out of the European war. And that would have changed history.

Fortunately, Hitler lacked the requisite imagination.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here. You must be a Troy Media Marketplace media subscriber to access our Sourcebook.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.