John F. Kennedy is often seen as the ultimate symbol of Irish-American success and social acceptance. And there’s much truth to that. Irish by ancestry and Roman Catholic by religion, Kennedy’s election to the U.S. presidency represented a breakthrough in status and prestige for an ethnic group that had once been viewed with suspicion.

John F. Kennedy is often seen as the ultimate symbol of Irish-American success and social acceptance. And there’s much truth to that. Irish by ancestry and Roman Catholic by religion, Kennedy’s election to the U.S. presidency represented a breakthrough in status and prestige for an ethnic group that had once been viewed with suspicion.

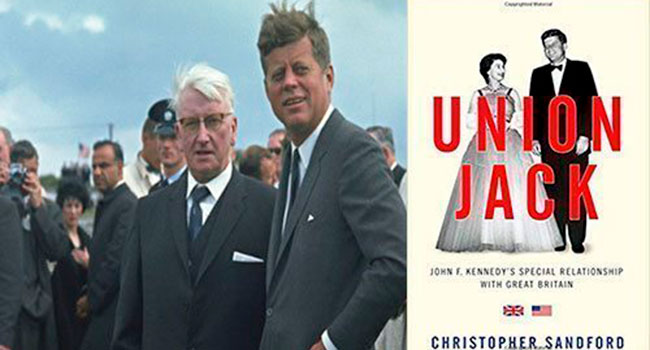

But understanding the personal Kennedy is more complicated. As Christopher Sandford’s Union Jack reminds us, when it came to temperament, interest and affinity, Kennedy was a pronounced anglophile.

Thomas Kiernan, Ireland’s ambassador to the U.S. during the Kennedy years, understood that. He said the president was “more British than Irish … Kennedy’s first reaction, if there were any even minor dispute between Britain and Ireland, would be to side with Britain.”

For all its astuteness, Kiernan’s observation lacked precision. Kennedy’s orientation was specifically English, not British. And it showed in the books he read, the people he admired, the friendships he made and the topics that engaged his interest.

| MORE IN BOOKS | |

| Fenians used Canada as an Irish revolutionary pawn By Pat Murphy |

|

| Two women defined by and celebrated for a single book each By Pat Murphy |

|

| ‘Radical Joe’ Chamberlain inspires new British PM By Pat Murphy |

When political journalist Hugh Sidey asked Kennedy for a list of his favourite books, David Cecil’s The Young Melbourne took pride of place. First published in 1939, it’s a biography of 19th century English politician William Lamb, who, as Lord Melbourne, will be familiar to viewers of the recent TV series Victoria.

Another Englishman, Winston Churchill, was Kennedy’s 20th century hero. That was an interesting choice in light of both the personal antipathy between Churchill and Kennedy’s father, Joseph, and his own youthful isolationism. But like many of his peers, Kennedy learned a particular lesson from the unfortunate denouement of 1930s appeasement, a lesson that informed his foreign policy perspective for the rest of his life.

And perhaps most important, there were the friendships and social relationships.

From his first visit to briefly attend the London School of Economics in 1935, Kennedy became enamoured with certain aspects of English life. There were lively political discussions, eccentric characters and visits to grand country houses. And there were parties with ample champagne, entertaining gossip and free-spirited, sexually available women.

The Cavendish family – one of the richest and most influential of England’s aristocratic dynasties – became a special favourite, no doubt partly because Kennedy’s sister Kathleen married into it. For his January 1961 inauguration, Andrew Cavendish and his wife Deborah – one of the famous Mitford sisters – were invited guests.

Of the many personal friendships, that with David Ormsby-Gore was probably the deepest. They met in 1938, when, in Sandford’s description, Ormsby-Gore was “in the midst of an academically glittering if debauched undergraduate career at Oxford.” And they remained close right up until Kennedy’s death, so much so that a resentful Vice-President Lyndon Johnson disdainfully referred to Ormsby-Gore as “the limey.”

It would be a mistake, though, to think that Kennedy’s affection for most things English represented a rejection of his Irish heritage. To him, there was no necessary conflict.

On his second visit to Ireland – a September 1947 sojourn at the Cavendish-owned Lismore Castle – Kennedy set out (with Pamela Churchill in tow!) to track down his great-grandfather’s relatives in Dunganstown, County Wexford. When he found the farmhouse, so the story goes, he held out his hand and introduced himself as “your cousin John from Massachusetts.”

And his 1963 presidential visit was one of the major events of mid-20th century Ireland. From his “distinguished son of our race” welcome by President Eamon de Valera on June 26 to his June 29 departure, Kennedy charmed and inspired wherever he went. People were proud and moved by his presence and he gave every impression of being entirely comfortable.

He would not, however, take the bait on the subject of partition and Irish unification. This refusal was consistent with a long-established inclination. In an address at a 1954 New York St. Patrick’s Day dinner, his reticence on that subject caused one disappointed attendee to liken the experience to “eating your soup with a fork.”

The euphoria surrounding the 1963 visit even gave rise to suggestions that Kennedy might establish a post-presidential residence in Ireland. But de Valera didn’t think so, privately observing that “there was no real sense of connection” and “that what we saw was the president’s charm and good manners rising to the occasion, not him preparing the groundwork to live here.”

De Valera was nobody’s fool.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.