Chretien’s assessment? “He looks good until you put him on the ice.”

Mulroney’s? “A great man and a victim of timing”

On the occasion of John Turner’s death in September 2020, a column of mine earned a gentle rebuke from a regular reader. The problem wasn’t that I’d said anything factually inaccurate. Rather it was what I hadn’t said. My reader thought Turner was a more accomplished and consequential man than I’d recognized.

On the occasion of John Turner’s death in September 2020, a column of mine earned a gentle rebuke from a regular reader. The problem wasn’t that I’d said anything factually inaccurate. Rather it was what I hadn’t said. My reader thought Turner was a more accomplished and consequential man than I’d recognized.

Steve Paikin’s immensely readable new biography – John Turner: An Intimate Biography of Canada’s 17th Prime Minister – brought this back to mind. Whether it has changed my opinion is a different matter.

First, a brief recap of who Turner was.

Born in 1929 and first elected to Parliament as a Liberal in 1962, he was prospectively seen as Canada’s version of John F. Kennedy. He ticked all the boxes – handsome, charming, vigorous and very modern. Surely he’d be prime minister one day.

|

| Related Stories |

| John Turner and the demise of gentlemanly politics

|

| John Turner had an unflagging faith in the people

|

Then along came Pierre Trudeau with his own unique brand of political sex appeal. Seemingly emerging from nowhere, Trudeau won the Liberal leadership in 1968, became prime minister and promptly scored a sweeping general election victory.

Still, Turner was deemed to be a man with big things ahead of him, serving Trudeau in two high-profile cabinet positions – justice and finance – and being generally viewed as the obvious heir apparent. Although he quit in 1975 to become a lucratively remunerated Bay Street lawyer, he had the aura of a prince in exile awaiting his moment.

Eventually, the moment did come when Trudeau retired in 1984 and Turner replaced him to become Canada’s 17th prime minister. But he only lasted 79 days.

Paikin neatly captures the nature and extent of Turner’s troubles, both during his brief tenure as prime minister and his subsequent run as opposition leader.

The Liberals had been in power for a long time, during which they’d accumulated a lot of baggage. It’s the sort of thing that happens to all parties that have extended periods in office.

And the Trudeau magic – so beguiling during the heady days of 1968 – had well and truly worn off. What was originally perceived as fresh and exciting now struck many as arrogant and domineering. Only a miracle could save the party’s skin.

The expectation in many quarters was that Turner would provide that miracle. Expectations, however, can be at odds with reality. This was one of those times.

The man who returned in 1984 bore scant resemblance to the image. The most generous interpretation is that almost a decade away from the political arena had left him rusty and out of practice. The alternative perspective is that he was always overhyped.

Paikin relates the reaction from an attendee at Turner’s first cabinet meeting: “Where was the powerful Bay Street lawyer, the outstanding finance minister, the big business candidate who would assure us a new lease on power?” Instead, there was “a prime minister who needed to be loved and surrounded with comradeship, like one sees on television in a male locker room after a great game of hockey.”

Following the rout in the 1984 general election, Turner – now opposition leader – was adrift within his own party. Paikin puts it this way: “There’s one thing about leading Canada’s natural governing party: they love you win or tie. Losing is not tolerated.”

Turner had two additional problems.

The Liberals had changed. While the party’s orientation could still be described as centre-left, the left part of that designation had assumed greater importance. Turner, in contrast, was a business-friendly Liberal who cared about things such as deficits. Lots of other Liberals didn’t.

And Turner was ideologically and personally alienated from two of the party’s most influential figures – Pierre Trudeau and Jean Chretien. The underlying reasons were many, including conflicting ambitions, incompatible personalities, and a history of real or perceived slights.

Suffice it to say that the knives were out after the 1984 election debacle. And Paikin takes us through an intra-party picture of almost unremitting hostility, culminating in a bizarre attempt to replace Turner as leader in the midst of the 1988 election campaign. When he lost again, his goose was cooked.

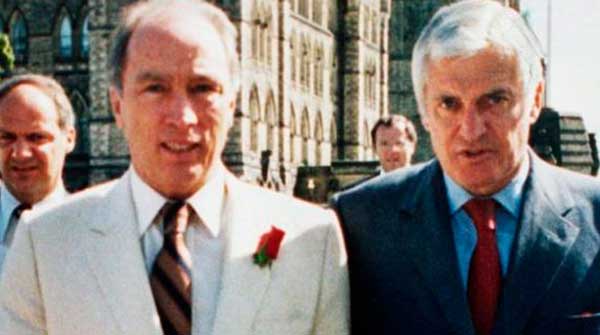

Two former prime ministers, both of whom competed against Turner, have offered contrasting bottom lines.

Chretien wasn’t a fan. Likening Turner to a Montreal Canadiens’ hopeful who fell short of expectations, Chretien’s assessment was brutally succinct: “He looks good until you put him on the ice.”

Brian Mulroney begged to differ. To him, “John Turner was a great man and a victim of timing.”

As for the truth, elusive though it may be, read Paikin’s book and see what you think.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.